Keeping warm in the winter was a common problem for residents of the plains, and different groups had different solutions to the problem. For instance, John W. Hartman came to eastern Nebraska in 1890 and got to know some of the first generation of settlers. Hartman wrote,

"John Gilbert was a stage-driver working for the government. . . . The Pawnee were great friends to John Gilbert. Many of their tribe would come each fall to make Gilbert a visit. In one of their visits, Gilbert went down to the timber where they were camped and setting around a little fire. Gilbert got a lot of brush and logs to put on the fire. The Indian chief said:

‘White man damn fool — builds great big fire and have to get a long ways from it. Indian builds a little fire and sets around it.’ "

Most settlers built fires in stoves to heat their houses, but the homesteaders didn’t have the same fuel sources they had back east or in Europe. Wood was precious. Coal was expensive. So what did they use?

As with their building materials, they used what they found at hand. If you lived by a stream, you gather wood. Hay, straw and even sunflower stalks were used. And someone discovered that "chips" — that is, droppings from either cows or buffaloes that had dried in the sun — burned pretty well in the stoves. So, the chips were used for fuel. All you had to do was gather them up. Piles of chips up to 10-12 feet high might be built next to the sod house.

James G. Eastman remembered some of his chores during settlement time.

"In the earlier days of our childhood we had a terrible time to keep warm. We never knew when a great storm would come up and just how the next day would be. My mother would send me out to pick up buffalo chips, sunflower stalks, and big weeds and sticks which we piled up for fuel. I have seen frost in Nebraska in July. Seen the leaves freeze off and all of our corn would be ruined. [On the other hand,] in 1903, 1906 and 1907 we plowed twelve months of the year and in these three years there wasn’t any snow at all."

These natural fuel sources were also used for cooking year round. Chips were a challenge. Women had to overcome the disgust they felt not only for gathering manure, but bringing it into the home and cooking with it. Chips and hay twists both burned hot but quickly. Keeping homes clean when using a chip-fired stove was a chore. As Charley O’Kieffe recalled:

"Here is the rundown of the operations that mother went through when making baking powder biscuits. ... Stoke the stove, get out the flour sack, stoke the stove, wash your hands, mix the biscuit dough, stoke the stove, wash your hands, cut out the biscuits with the top of a baking powder can, stoke the stove, wash your hands, put the pan of biscuits in the oven, keep on stoking the stove until the biscuits are done (not forgetting to wash the hands before taking up the biscuits)." — From Western Story: The Recollections of Charley O’Kieffe, 1884-1898. Lincoln: U of N Press, 1960.

Because this kind of fuel burned quickly and produced a lot of ash, there was a standing joke in the sand hills of Nebraska:

A visitor asked a settler how his family was. The settler replied that the children were all right, but he hardly knew about his wife since theirs was a ‘passing acquaintance’. He said, "We see each other, but only as she is going out with a pan of ashes and as I am coming in with a bucket of cow chips. It keeps both of us on the go to keep from freezing. With all the hustle and bustle, we have no time for idle visiting."

Even with all that work, sometimes the stove couldn’t keep up with the cold. John Hartman also wrote,

"The winter of 1862 was very severe and cold with plenty of snow. It was almost impossible to keep warm with old-style cook stoves and green wood. My sister’s feet frosted sitting by the stove with quilts around her."

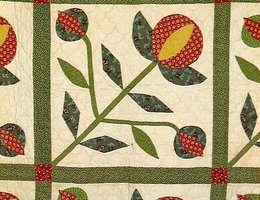

Obviously, quilts were practical items intended, on one level, to keep their owners warm. On another level, they were (and are) works of art with visual decorations that go well beyond what was necessary to keep warm. Quilting was an extremely popular pasttime for women in 19th century America. They had the added advantage of being put on the bed in order to keep warm. Catherine Eby Miller handmade this quilt in the mid-1800s. The pomegranate or love apple pattern was popular from the 1840s into the 1860s. This appliquéd cotton quilt was brought by Catherine’s daughter, Elizabeth Sageser, to Chambers, Nebraska in 1886 where it was used in a sod house.

Lizzie Lockwood’s parents settled in Nebraska in 1870, and she remembers how common quilting was:

"If a girl hadn’t started to piece a quilt by the time she was eight or ten years old, we just didn’t have anything to do with her." — [Source American Memory, WPA]

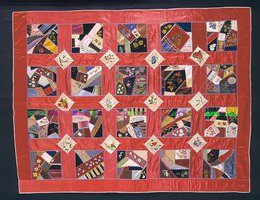

Clarissa Palmer Griswold came to Nebraska in 1885 and her quilt is now in the collection of the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Clarissa made her quilt during the year that she “sat” her claim under the terms of the Homestead Act.

Clarissa recalled in her memoirs that, as she grew up in Minnesota, her imagination was fired by stories of young people finding their fortunes in the West. She reveled in stories of girlfriends living together in a cabin built on adjoining claims, homesteading together. A friend, Mrs. Sellers, invited Clarissa to visit her home in Ainsworth, Nebraska, to see the West and recover her health. Clarissa arrived in September 1885. In October, she went further west to Valentine and filed a claim on a parcel of land — without ever seeing it — even further west near Harrison. She had some money, so she hired a crew to build a log cabin, an unusual sight on the plains. But she still had to use newspapers for wallpaper and gunny sacks for carpets.

Clarissa stitched her quilt from a variety of silk fabrics sent to her by friends and family members. The multicolored scraps of velvets, taffetas, brocades, and damasks, as well as prints, plaids, and stripes, combine in a montage of patterns and texture against the brilliant scarlet sashing.

She painted the flowers on the quilt from wildflowers she found on her claim. She wrote, “That first summer, I copied these flowers with oil paints on silk and velvet sent me from home. The crazy quilt I decorated and pieced then is now quite a showpiece to be handed down.”

In 1886, Clarissa married Dwight Griswold, a store owner in Harrison. Dwight went on to become a banker in several western towns. Their second son, Dwight Griswold Jr., became a U.S. Senator and Governor of Nebraska.